The Nkomazi community came together to address their concerns and build peaceful relationships

September 14, 2009 – “They need to come and cough out what really hurts them.” These words, from a participant in the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s community conversations on social cohesion, aptly express what the series is for. It creates a safe space where ordinary people can open up and talk – and start to act constructively.

The Foundation and its partners (the Masisukemeni Women’s Organisation, the Somali Association, the Mpumalanga Council of Churches and the Leandra Advice Office) held a community conversation in Naas, a large developing settlement in Nkomazi, Mpumalanga, on August 27, 2009. The event was one of a series of dialogues being held around South Africa to explore ways in which communities made up of a number of different nationalities can address their concerns and build peaceful relationships. The series was launched in response to the xenophobic conflict of 2008.

The community conversation in Nkomazi followed one held on June 6, 2009 in Delmas, also in Mpumalanga, and presented an opportunity to compare community responses to the pressures and benefits brought by migration.

In the Delmas conversation, people tended to make their input on the basis of their political affiliation. In Nkomazi, though people had strong political loyalties, they engaged in the dialogue more independently as individuals.

Nkomazi, located about 350km east of Gauteng, is an area wedged between Mozambique, Swaziland and the Kruger National Park, in the Maputo Corridor. Families and communities straddle these borders and, in addition to people of Mozambican origin who have lived there since the 1980s, there are more recent immigrants from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Nigeria, Somalia and Ethiopia.

The population of Nkomazi is concentrated in the underdeveloped southern section, where more than half the people are under the age of 19, the unemployment rate is 50% and 6.8 people are dependent on each income. Most of the households earn less than R1 000 a month. There is considerable pressure on resources and services.

About 70 people attended the community conversation in the Kamaqhekeza Community Hall. Most of those present were South African nationals and concern was expressed over the limited representation of migrants and of government officials.

The main purpose of the meeting, which is the first in a process of dialogue, was to establish trust among the various groups and individuals, and to begin building relationships.

For these conversations to work, people have to turn up, they have to trust each other, they have to be thoughtful and honest, and they have to listen. And this is where certain tools come in handy.

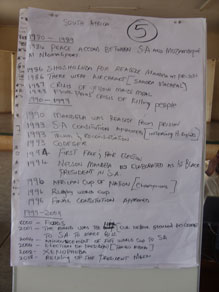

Using tools from a methodology called Community Capacity Enhancement, the conversation facilitators encouraged people to reflect on the social and political struggles of South Africa and other African countries, and how these historical events had made an impact on present realities.

It emerged that this particular community prided itself on its knowledge of the history of the area, and some of the people at the conversation were former liberation struggle combatants with personal experience of exile.

Some of the historical events mentioned in this exercise were: the imprisonment and later release of Nelson Mandela; the death of Mozambican President Samora Machel; civil war in Nigeria; famine in Ethiopia; civil wars in Mozambique, Angola and Somalia; genocide in Rwanda; floods in Mozambique; instability in Zimbabwe, Madagascar and Guinea Bissau; violence in Kenya; the coming of democracy to South Africa; the election of Jacob Zuma; and major sports events.

The conversation participants were able to make connections between their own local concerns and the effect of external events and migration trends. They discussed the purpose of African struggles, unity, humanity, and questions of rights and belonging.

“Watching people from the same region killing each other showed how quickly we forget,” said one Mozambican participant. “We forget why Machel was killed and what he was fighting for – the independence of all Africa.”

The community also spoke about perceptions of crime: corruption of officials in the issuing of identity documents, illegal activity among migrants, South Africans cheating migrants, and so on. Exploitation was mentioned as happening both ways – immigrant business people paying low wages and immigrant workers being poorly paid by South Africans. The perceived reluctance of non-South Africans to integrate was a concern – there was even a comment about the establishment of Muslim cemeteries. There was also a question of whether migrants should be treated as one group or distinguished from each other.

The community agreed during the conversation that:

- The Department of Home Affairs should audit its records to verify the authenticity of information on IDs and marriage certificates which may have been issued fraudulently.

- The government must take action on corruption, such as officials allocating houses without regard to the official waiting list.

- Joint structures (comprising locals and migrants) should be set up to follow up on recommendations raised during such conversations.

- Non-nationals should be assisted in organising themselves to integrate with locals and deal with undesirable practices.

The Nkomazi community was keen to have a forum where they could articulate local challenges such as service delivery, unemployment and corruption. It was clear that they did not feel “heard”.

“Our lawmakers need to understand us before they take positions on our behalf,” said one person.

Initiatives to build social cohesion among migrants and host communities must take the locals’ own challenges into account. As one participant put it, “Before we welcome others, we must welcome ourselves – our children, orphans, widowers. If we cannot accept our [South African] neighbours, how can we accept others?”

“I was born here,” said another South African, “but I am being discriminated against due to my level of education.”

The historical timeline exercise enabled the community to view their concerns as common challenges facing both migrant and host communities that could only be overcome through collective effort. “We are not saying we don’t want our African brothers and sisters, but that we need to create a joint platform to address our difficulties,” one member said.

It was this collective participation that people viewed as the key towards addressing many of the concerns that induce tension between migrant and host communities.

In addition, community members saw this conversation as a way through which the worth of each individual could be restored in the eyes of the entire community. “Through this we can begin to understand the basic principle in life – you should do unto others what you want them to do to you,” one participant concluded.

The facilitation team committed to keeping government departments and non-governmental organisations informed of what came out of the community conversation and continuing to encourage them to participate in upcoming conversations.

Another conversation is scheduled for October 12 in Nkomazi.