Life & Times of Nelson Mandela exhibition

This exhibition begins at the front entrance of the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s Centre of Memory and ends in what was Nelson Mandela’s post-presidential office from 2002 to 2010.

This exhibition begins at the front entrance of the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s Centre of Memory and ends in what was Nelson Mandela’s post-presidential office from 2002 to 2010.

Curated by the Foundation’s Research and Archive team and designed by Trace Media, the exhibition offers a perspective on Mandela’s life within the contexts of colonialism, apartheid and democracy.

The narrative is carried by short text panels and a diverse range of other elements – artefacts, documents, photographs, film, sound recordings and special installations.

Two elements make this exhibition unique:

-

The displays of artefacts and documents from Mandela’s private archive

-

The walk-in feature of Mandela’s post-presidential office, preserved as it was the last time he used it

For the Foundation the exhibition must remain a work-in-progress, constantly being refreshed, updated and enhanced.

It will always be brought into conversation with smaller-scale, temporary exhibitions mounted in the adjacent foyer area.

The exhibition’s narrative

Colonialism

From the 1500s, European powers began establishing colonies in other parts of the world. By the beginning of the 20th century, most of Africa had been colonised. Long struggles for liberation saw the start of the independence process from the early 1950s, but in some countries formal colonial government was replaced by various forms of European settler rule.

South Africa was the last country in Africa to have such rule ended by a transition to democracy. In the 17th century, the Dutch colonised the Cape. On the back of unsuccessful wars of resistance by indigenous black polities, for the next three hundred years what was to become the country called South Africa experienced rule by the Dutch, the British and independent settler republics.

In 1910, Britain oversaw the establishment of the Union of South Africa, a classic settler state in which only whites enjoyed full rights of citizenship. Colonial socio-economic structures and relations remained resilient for decades after 1910. It could be argued, of course, that for black South Africans the Union was just another form of colonisation. Certainly when Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born in 1918, it was into a colonial setting.

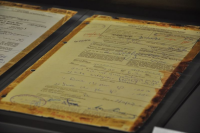

Items on display include Mr Mandela's personal artefacts, including the Warrant of Committal from his arrest and conviction.

Apartheid

South Africa’s capitalist development in the first half of the 20th century required the segregation and control of black communities.

In 1948, an Afrikaner nationalist class alliance assumed power with a broad racial ideology offering the protection of the "Afrikaner people" and also the maintenance of white supremacy. The term "apartheid" was used by the National Party as an election slogan in 1948, and although over the years substitute terms were employed by both the party and the state, "apartheid" stuck as the term of choice worldwide for a system of governance and a legitimising ideology that endured in essence until 1994.

Apartheid has been most usefully described as a form of racial capitalism in which racial differences were formalised and in which society was characterised by a powerful racially defined divide. Among the world’s racial orders, South Africa’s was unique in its rigidity and in its pervasiveness.

From the late 1970s, the apartheid system began to unravel as black resistance intensified, international pressure grew, and forces within capitalism demanded reform. By the late 1980s, it was in profound crisis and the primary instruments of power had become the suspension of law and the unleashing of state terror on oppositional groupings.

Items on display include Mr Mandela's personal papers and photographs.

Finding the enemy: 1918-1944

Rolihlahla Mandela was born into an aristocratic family in the rural Eastern Cape, the son of a chief. After his father’s death he became the ward of the acting Thembu King, Jongintaba Dalindyebo, who raised him at the Great Place in Mqhekezweni. He also carried the clan name Madiba, the circumcision name Dalibhunga, and the English name Nelson (given to him by his teacher on his first day at school).

He attended Methodist mission schools before enrolling for a Bachelor of Arts at the prestigious University of Fort Hare in 1939. Effectively expelled from the university for protest action, he left with his studies incomplete.

In 1941 he arrived in Johannesburg, having fled an arranged marriage, and after a brief interlude as a gold mine security guard, he finished his degree by correspondence and worked as a clerk in a law firm. His thinking and values were a fusion of the traditional and the modern, the indigenous and the Western. In the townships of Johannesburg he was exposed to the poverty, deprivation and brutality of black urban life.

His earliest political influences were Gaur Radebe, Walter Sisulu and Anton Lembede. Sisulu became his mentor and a lifelong comrade and friend. In 1944 he joined the African National Congress when he co-founded its Youth League. He aligned himself with the Africanists, who resisted cooperation with communists and organisations representing "non-Africans". It was at the Sisulu home that Mandela met and fell in love with Walter’s cousin, Evelyn Mase. They were married in 1944 and had four children.

A desk calendar from Mr Mandela's prison cell is on display.

Facing down the enemy: 1944-1962

Mandela quickly rose to leadership positions within the African National Congress. By the late 1950s, he was a prominent public figure and a thorn in the apartheid regime’s flesh. His work as an attorney with OR Tambo in South Africa’s first black legal firm mostly involved defending black victims of the apartheid system.

As volunteer-in-chief in the 1952 Defiance Campaign of the ANC and the South African Indian Congress, he led thousands to break apartheid laws. He was frequently arrested and banned. The Defiance Campaign trial saw him and 19 others sentenced to nine months, suspended for two years. He was one of the accused in the Treason Trial (1956-1961), but again walked free.

The ANC was banned in 1960 after the Sharpeville Massacre, and in 1961 Mandela went underground. He became the first commander-in-chief of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC. The liberation struggle had become Mandela’s life and the ANC his family.

Under the tutelage of Sisulu and working with communists like Michael Harmel, Bram Fischer, Yusuf Dadoo, Ahmed Kathrada and Moses Kotane, Mandela shed his Africanism and embraced the non-racialism of the Congress movement. Mandela sacrificed domestic life to the struggle. His marriage to Evelyn collapsed, and in 1958 he married Nomzamo Winifred Madikizela, with whom he had two children. His new family was also to suffer from his absence.

Learning the language of the enemy: 1962-1985

The Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Nelson Mandela is on display.

In 1962, Mandela was sentenced to five years in prison for leaving the country illegally and for inciting a strike. The next year, from prison, he became accused number one in the Rivonia Trial, which saw most of the senior internal leadership of Umkhonto we Sizwe sentenced to life imprisonment for sabotage.

Mandela would be a prisoner for over 27 years. By the time he was released he was the most famous political prisoner in the world, and a global symbol for the anti-apartheid movement.

He used his time in prison to further his studies, read widely, reflect deeply, and learn as much as he could about Afrikaner histories and cultures. He became proficient in Afrikaans, engaged his jailers intensely, and nurtured deep friendships with fellow prisoners Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Eddie Daniels, Laloo Chiba and Mac Maharaj.

From the outset he was regarded as the leader and representative of African National Congress (ANC) prisoners, a position he used to sustain unrelenting pressure on the prison authorities to improve conditions. He led ANC engagements with new generations of political prisoners.

In the first few years of his incarceration, Mandela lost both his mother and his eldest son. He was also devastated by the apartheid regime’s relentless persecution of his young wife and children. Using every means available to him, from writing letters and getting his lawyers to intervene, to prison visits and financial assistance from supporters, he reached out to his family, nurturing them both collectively and individually.

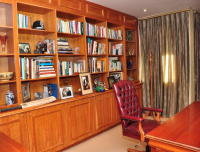

Mr Mandela's post-presidential office.

Talking to the enemy: 1985-1994

In 1986, Mandela took the fateful decision to inaugurate "talks about talks" with representatives of the apartheid state. He did this before consulting with his comrades in prison or African National Congress President OR Tambo. It was a moment of great leadership, but also of great danger.

From 1985, the state separated him from his fellow prisoners and brought all the resources of the state to bear on using him to best advantage as negotiations with the ANC loomed. Even though Mandela established lines of communication with Tambo and other leaders, comrades outside feared that he might have "sold out".

They need not have worried – he managed the process masterfully, and ensured that it was integrated with other "talks about talks" processes that emerged from 1987. After his release from prison in February 1990, he very quickly took the reins, became the President of the ANC when Tambo stepped down with health problems, and led the formal negotiations with the National Party and its allies.

Throughout the period 1990-1994, Mandela travelled the world, receiving adulation wherever he went. He garnered support for the negotiation process, raised funds for the ANC, received a Nobel Peace Prize, and published his best-selling autobiography.

Again, there was little space in his life for the private, the personal and the domestic, and his relationship with Winnie Mandela fell apart. They separated in 1992 and divorced in 1996. He found it difficult to restore intimacy with his children. He experienced a deep loneliness.

Mr Mandela's reading room and a selection of books on display.

Democracy

Resistance to apartheid was led by the African National Congress and allied organisations. The considerable energies of African nationalism were increasingly channelled into the struggle for a democracy defined by non-racialism. There were four pillars to this struggle: armed resistance, underground work, international solidarity and mass mobilisation. The apartheid regime was not overthrown. When it became clear that the slow disintegration of the apartheid system could not be stemmed, the regime engaged its opponents in a process of negotiated settlement.

In February 1990, the ANC and all other outlawed oppositional organisations were legalised, and Mandela was released from prison. This began a period of formal negotiation leading to South Africa’s first democratic election in April 1994. Although the ANC, led by Mandela, won a sweeping victory in that election, it would manage the first five years of democracy-building through a Government of National Unity.

The nature of the transition to democracy meant that there would be no dramatic dismantling of the apartheid system. Rather, the new would be built out of the old through processes of transformation and reconciliation. These processes were given a powerful symbolic embodiment in the person of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela.

Mr Mandela's post-presidential office.

Discovering new enemies: post-1994

After South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, President Mandela formed a Government of National Unity led by the African National Congress. His presidency (1994-1999) focused on the challenges of nation-building, reconciliation and reckoning with the past. Rebuilding South Africa’s international reputation was also high on his agenda.

He relied on Deputy President Thabo Mbeki and his Cabinet to look after governance and the nuts and bolts of transformation. The challenges were many: apartheid socio-economic patterning was resilient; the damage wrought to the social fabric by centuries of oppression was profound; and there was considerable vested interest in avoiding significant restructuring of the state and the economy.

President Mandela voluntarily stepped down after one term in office to make way for a new generation of leadership. But his acute sense of unfinished business would not allow him to retire from public life. He founded charitable organisations to continue his work.

He contributed to finding peace in international conflicts. He spoke out on issues as diverse as HIV/AIDS, corruption, poverty, the Iraq War and Zimbabwe. By his 90th birthday in 2008, he was a global icon of unparalleled stature. In 2009, his birthday was declared Nelson Mandela International Day.

In 1998, Mandela married his third wife, Graca Machel. From 1999, he devoted more time to domestic life, and was often surrounded by his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Click here to view a gallery of images of the exhibition.

For Madiba with Love exhibition

This temporary exhibition, by acclaimed American photographer David Turnley, was launched on 2 February 2014 and was on display at the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory until the end of April 2014.

Turnley, who has won a Pulitzer Prize, two World Press Photo of the Year awards and many other accolades in his career, enjoyed a unique and close relationship with the Mandela family, having met Winnie Mandela in 1985.

For Madiba with Love is a selection of his photographs from the period 1985-1994, depicting both the Mandelas and the South Africa of the time. The photographs on display are accompanied by captions detailing Turnley's thoughts and reflections.